You're using an outdated version of Internet Explorer.

DOWNLOAD NOWWednesday, October 31, 2018

Source : The Wire

The former prime minister's role in shaping India’s society by attempting to give succour to those who needed it most, and in consolidating and expanding the country's comprehensive national power when imperialism was doing everything to undermine it, is an invaluable one.

The former prime minister's role in shaping India’s society by attempting to give succour to those who needed it most, and in consolidating and expanding the country's comprehensive national power when imperialism was doing everything to undermine it, is an invaluable one.

When Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was shot dead on October 31, 1984, about three weeks before her 67th birthday, the country had wept. Her political opponents – on the Right and the Left – couldn’t understand this, and neither did the liberals.

They continued to be cutting about her in her death and long after it, overlooking her enormous across-the-board contribution to India. Her time in office came to be viewed exclusively through the lens of the Emergency, and the accompanying weakening of some institutions in that period.

The criticisms remain valid. But assessing the former prime minister by the Emergency metric alone cannot be the basis of a dispassionate assessment, which is still awaited. Indeed, a strange animus toward Indira Gandhi continues to be harboured by her mutually antagonistic opponents who, in spite of their ideological differences, were not above doing business with one another when waging battle against her.

Nearly two generations have gone by since the passing of Indira Gandhi, but her public evaluation by the Left and the liberal folk continues to be on the same footing as that of the market Right and the communal Right. In private, though, some may speak a different language.

A cabinet minister of the Lohia persuasion in the Vajpayee government once told this writer that only on becoming a minister was he able to fully grasp the high degree of idealism, fidelity to India’s cause in the face of imperialistic challenge to this country’s personality and the pragmatism and fearlessness with which Indira Gandhi had led the country in a turbulent era “though we kept abusing her, and dare not speak out our minds even today.” The fear of questioning one’s own past frightens political people more than others.

What Indira Gandhi was to ordinary people

In sharp contrast to the politicos were the ordinary folk, most certainly the urban and the rural poor, and among them the Dalits and Muslims especially. They backed Gandhi to the hilt, punished her for the Emergency by voting her out and then renewed their affection after extracting recompense. Before Gandhi, the country had wept on the passing of only two leaders – Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru – and after her, none at all. The museum housed in the building in which she had lived and died in New Delhi still receives throngs of visitors in tourist buses from all over India.

In sharp contrast to the politicos were the ordinary folk, most certainly the urban and the rural poor, and among them the Dalits and Muslims especially. They backed Gandhi to the hilt, punished her for the Emergency by voting her out and then renewed their affection after extracting recompense. Before Gandhi, the country had wept on the passing of only two leaders – Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru – and after her, none at all. The museum housed in the building in which she had lived and died in New Delhi still receives throngs of visitors in tourist buses from all over India.

The reason for the reverence – and perhaps there is no better word – to her memory among ordinary people is that the key domestic policies she pursued (unlike the cruel joke of demonetisation played on the poor in the Modi era) gave the ordinary Indian a sense of some power and not just a little hope.

There was envy of this on the Left who may have themselves wanted to do some of the things that Indira Gandhi did if they had the chance, so they latched on to the Emergency and its excesses – when these came – in order to harshly criticise her.

Why the Right hated Gandhi

It was precisely on account of many of these policies (for example bank nationalisation) that the Right, including the Hindu Right (who saw their potential constituency walking to Gandhi’s corner), had opposed her right through her term, and not just during the Emergency. In some degree, she was attempting to alter the terms of trade away from the owning classes and in favour of the common folk. This produced hatred for her in the right-wing of Indian politics.

Thus, to the Right too, the Emergency came as an opportunity to seek political reparations from the idea of Indira Gandhi, and on the larger canvas the Congress, even decades after her assassination. The crudest manifestation of this has been the raking up of the Emergency by Prime Minister Modi in every year of his tenure. Quite extraordinarily, 40 years after the event. Evidently, he is not sure that his own drum will sound loud enough even if he beat on it incessantly (as he does).

The irony of Modi decrying the Emergency

But the irony of Modi decrying the Emergency is not lost on those who had opposed the Emergency regime. It is a hypocrite’s lament. Indira Gandhi had used the existing laws to upstage parliament and the democratic institutions. Modi has produced similar results without going the same route. His opponents are not behind bars, but the coercive state has done its best to silence them by keeping them tied down with criminal cases.

But the irony of Modi decrying the Emergency is not lost on those who had opposed the Emergency regime. It is a hypocrite’s lament. Indira Gandhi had used the existing laws to upstage parliament and the democratic institutions. Modi has produced similar results without going the same route. His opponents are not behind bars, but the coercive state has done its best to silence them by keeping them tied down with criminal cases.

The general run of the media has kept its critical faculties largely suspended in the face of the destruction of the country’s democratic ethos chiefly because the Modi quasi-dictatorship has in considerable measure worked against the interest of the poor and in favour of big industry. A top gun of industry who owes the banks Rs 20,000 crore is a VIP with the prime minister. On account of its ownership patterns, the media cries foul when money is spent from the treasury on the needy but remains unruffled when the rich resort to illegality.

In the main, journalists as individuals are not in accord with this approach but they have to lump it. Since sections of industry see the Modi regime working for their interests on a pretty much exclusive basis, they are also unmoved by the deliberate and crude efforts to expand the communal agenda in the Modi era, and the media as an institution goes along, though, as elections approach and the prime minister’s popularity is perceived as faltering, some effort at correction is occasionally seen these days.

But the most popular sport for the media in the last five years has been to mount a no-holds-barred attack on Modi’s political opponents and ruling party dissenters. The reality of Erdogan’s Turkey or Xi Jinping’s China is India’s reality in many respects today. The 15 years of Indira Gandhi as prime minister were vastly different.

Also, unlike the present, there was no effort to turn the country on its head by pushing for a conscious transformation of the society and the Indian state through the aegis of political fanatics and gangsters seeking justification for their barbaric and violent actions through a notoriously false depiction of religion, instead of an appeal to the democratic urge and spirit.

Not only did Indira Gandhi seek to alter the lives of ordinary people through governmental intervention for much of her time in office, but she also altered South Asia’s strategic space to India’s long-term advantage by helping mid-wife the creation of Bangladesh and the concomitant halving of Pakistan.

She fought back with tenacity and gumption the politico-military challenge thrown her way by the US-led Western powers (and their then ally China) in 1971-72, seeking to intervene on Pakistan’s behalf, as they had done in 1965, and earlier in the 1947-49 period and for years afterwards on the Kashmir question.

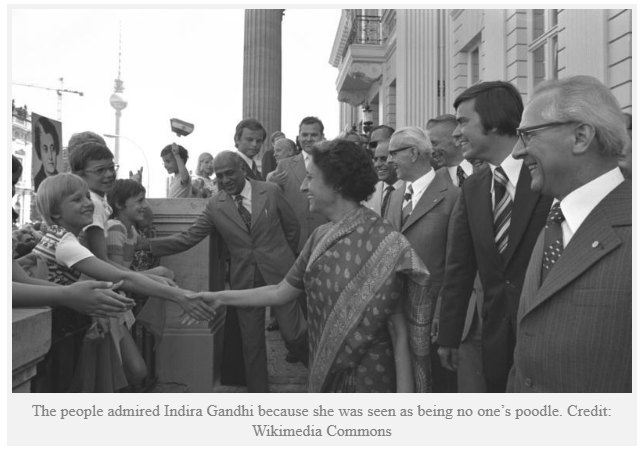

Indira Gandhi entertained no political anxieties in reaching a political accord with the Soviet Union, the pre-eminent communist power, without losing her faith in the democratic order. The people admired her because she was seen as being no one’s poodle – neither of the Americans’ nor the Soviets’. What a far cry from the present day.

The Emergency

The Emergency does break the record, however. This is for two specific reasons: one, the suspension of civil liberties and fundamental rights; and two, the assault on the poor through the sterilisation campaign pushed through by her younger son Sanjay Gandhi who had emerged as an extra-constitutional authority.

The Emergency does break the record, however. This is for two specific reasons: one, the suspension of civil liberties and fundamental rights; and two, the assault on the poor through the sterilisation campaign pushed through by her younger son Sanjay Gandhi who had emerged as an extra-constitutional authority.

In the election of 1977, the poor punished her on both counts as she lost her own parliament seat, although just two years later they would bring her back by throwing out lock, stock and barrel the sorry regime that had replaced her’s (one in which the RSS failed in its political bid to capture the high ground after having commandeered the anti-Emergency movement).

There was perhaps appreciation among the wider public that if Indira Gandhi had brought in the anti-democratic 19-month Emergency regime, it was she who rescinded it, ruing what it had produced. It needed a democrat’s conscience to do that. At a press conference in London later, she was to characterise that period as “a disaster”.

Indira Gandhi’s role in shaping India’s society by attempting to give succour to those who needed it most, and in consolidating and expanding India’s comprehensive national power when imperialism was doing everything to undermine it, is an invaluable one.

In her stride she took in a war with Pakistan, a fierce famine, the oil shock of 1973 that had crippled the world economy and a Pakistan-stoked separatist militancy in Punjab (which eventually claimed her life). Were it not for the Emergency, she might have had a surer basis to inheriting the mantle of revolutionary democracy.

But warts and all, Indira Gandhi still reminds us, as we mark another anniversary of her tragic passing, that a strong leader is one who shows compassion for the ordinary people of the land and is unafraid to take on those who challenge this premise.